Canyon de Chelly: First Memory Time Begins

A thunder cloud-cannon explodes somewhere overhead. Cottonwoods tremble in a rising wind, then wave their arms wildly in the invisible turbulence. And here am I, a thousand feet below the rim of red earth, sandstone cliffs towering above my little human figure, brilliant blue sky canopy above. Suddenly out of nowhere, a huge bucket of rain dumps down, sending me scurrying to the canyon wall for protection, back flat against the sun warmed rocks. But there is no escape. Waterfalls materialize in every direction, crashing down in a gushing symphony where there was only dry bareness before….a scene from the creation story when time began. Then the wall which is just barely sheltering me from the storm becomes a vertical ocean, rippling waves of water propelling down the cliff face behind my back] onto the canyon’s sandy floor. As the drama unfolds around my feet, tiny desert frogs appear from the sand where they are buried, waiting for this precise moment in time.

The moment is over almost as soon as it starts, this desert madness and miracle of passing storm. Sun sparkles over wet leaves, now glistening and refracting the light in delight at the welcome moisture. At least that is how I am feeling as I breathe in the fresh fragrance of wet sand, sagebrush and juniper. Waterfalls slowly recede, their crashing, gurgling noise passing like a dream. Frogs return to their subterranean hideouts…and I step out into this new world, like everything else in this desert more alive in the radiance that only rain can bring.

Canyon de Chelly, Arizona. Just a name on a map to many, and not the name it is called by those who have lived here for generations. To the Dine, this is Tseyi, or “inside the rock,” a place that echoes with memories of their ancestors and the ancient cliff dwelling Pueblo people. Their voices whisper in the winds that wend their way through willows, cottonwood and Russian olive trees, past coyotes howling their songs under starry night skies and down trails and pathways known only to those for whom this place is home. But the canyon holds memories for me as well, experiences that have changed the course of my life. Those experiences are the subject of future blogs that will include visits with my service learning program, Earth Walks

My first visit to the canyon was in 1991, assisting a tour led by a guide from the Santa Fe, New Mexico area. Our group overlooked the awesome canyon, visited the National Park Service museum and learned about its history and geology. All well and good, but that was only a brief introduction to one of the longest continuously inhabited places in North America, and not the heart and soul of the canyon. I was to learn more about that in the years to come. History and geology are important, though.

Perhaps geology is a bit more objective in the telling: The de Chelly sandstone was laid down during the Permian period over 200 million years ago. The formation is unusual because it is not horizontally deposited but rather as a cross-bedded formation composed of many steeply dipping wedges, typical of windblown dune deposits. The canyons were carved over millennia by erosion from the Tsaile and Whiskey creeks forming Chinle Wash, creating awesome vertical walls. The area encompasses a long three-armed canyon on the northwest slope of the Defiance Uplift sloping to the west where the de Chelly sandstone plunges under the land just east of the town of Chinle.

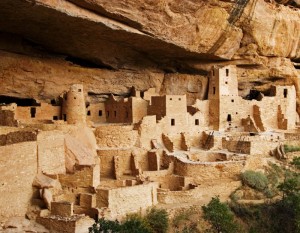

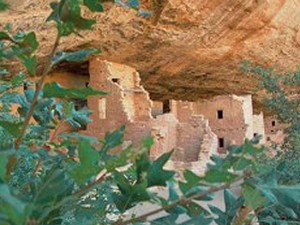

Now for history, which is more subjective and depends on who is doing the telling. I will try to do some justice based on what academic research I could find. For nearly 5,000 years people have used the canyon as a place for campsites, shelters and permanent homes. Artifacts and rock imagery of the Archaic and Basketmaker people have been found in the canyon. According to anthropologists and archaeologists the first settlers built pit houses that were replaced with more sophisticated homes built into south-facing alcoves of the canyon walls to take advantage of sunlight and natural protection. Research indicates Pueblo people left the area in the mid-1300s to seek better farmlands. The Hopi, descendants of the original Puebloans in the canyon, migrated to the area in the 1300-1600s, and then left to settle on mesa tops to the west.

For the record, researchers have long used the word “Anasazi” to refer to the ancient settlers of the area. Because that word in the Dine language often translates as “ancient enemies,” it gives offense to the Hopi and other current-day Pueblo descendants. The word now most often used is “Ancestral Puebloans.”

The Dine came to the area around 1700 and have lived there ever since, except for the tragic and brutal event known as the Long Walk when they were force-marched into exile at Ft. Sumner in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. Reportedly there had been a long history of trading and raiding among the various indigenous tribes and then later with Mexicans and peoples from the United States. Sprinkled throughout that history were broken promises and treaties. Be that as it may, the U.S. decided to put an end to the Dine resistance to their authority and in the winter of 1864 Army Colonel Kit Carson arrived on a scorched-earth mission to expel them from their native homeland.

Dine guide Daniel Staley with weaver Kathryn Paymala

Dine guide Daniel Staley with weaver Kathryn Paymala

It’s hard for me to imagine this where it is now serenely quiet, but instead of the calls of ravens and hawks, the canyon walls must have echoed with thundering horse’s hooves, gunfire and rampaging violence as Carson’s men torched cornfields, captured prisoners and chopped down some 2,000 peach trees. The Dine—including women, children and elders—were then forced to walk in bitter cold 400 miles east to Ft. Sumner. There they remained for four years in deplorable conditions of captivity before being released to return to their homeland. Many people fell ill during the relocation. Many died. It is a shameful atrocity and a sorrowful chapter in chapter in history.

It is said that on their return when the Dine reached the crest of the mountains of Albuquerque and on the horizon saw Mt. Taylor–known to them as Tsoodizil (Blue Bead or Turquoise Mountain)—they fell to the ground in prayer and gratitude. I think of my home as a physical address where I live or the town where I was born.

But talk with a traditional Hopi or Dine person and the thing called home will be a different story, layered with myth and meaning, some of which the English language cannot begin to express.

Because the streams running through Canyon de Chelly are not raging torrents like the Grand Canyon’s Colorado River, it has long supported farms and homes. Anasazi dwelling sites etched out of the vertical cliffs are found throughout the area accompanied by rock art petroglyphs and pictographs on the copper-hued walls, weathered into luminous “desert patina.”

One day while walking in the canyon with Dine guide Daniel Staley who has now become a friend, I was told: “When there is only one creation story left, it will be the end of the world.”

I won’t pretend that I know or understand the venerable complexity of Dine cosmology. But I do know that Grandmother Spider—who some say wove the web of creation for First Man and First Woman—has been a presence in my life since graduate school in 1971, long before I moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. It’s a tale I’ve told in other Earth Walks blogs. Here in Canyon de Chelly there is a towering monolithic spire called Spider Rock that I’ve visited repeatedly over 30 years, and in future I’ll share some of my experiences with this iconic sandstone tower.

Earth Walks takes guided journeys to Canyon de Chelly every year, led by Daniel Staley and his family members. Come join us! Go to the website at https://earthwalks.org/ to sign up for future service and travel activities.