Earth Walks In Canyon de Chelly 2025

A wonderful journey this May, 2025! On the way we stopped at the powerful volcanic formation called Shiprock.

Our local guides led us on a hike into the canyon and we stopped for lunch at Spider Rock, one of my places of personal reflection. One of our participants brought his large telescope for a Star Party on the rim of the canyon. Dine (Navajo) park ranger Justin shared the cultural cosmology of the stars, giving us a wonderful perspective. He is a runner and does so even in winter, drawing inspiration from the stars–as did we!Our last day was spent with friend Esther and her family at their ranch in Black Rock–and they all truly “rock”! Our thanks to them and so many others along the way. Plans are to return Memorial Day 2026–let me know if you would like to join the journey.

Happy Trails!

Doug Conwell

Category Archives: Earthwalks events

Chaco Canyon Journey 2024

The last day of our journey we walked in early morning silence up the path to Casa Rinconada, the Great Kiva. As we walked up, about 12 elk were walking down the mesa. One of those amazing sacred moments. At the kiva, we shared quiet moments of reflection and ceremony. Ines played her hand made buffalo drum, I played the Native American flute and Michael then intoned the haunting notes of his handpan. Then it was time to return, back to the campsite and back home after a wonderful experience together.

Come join us in 2025 when we return to Chaco…and maybe so will the elk!

Chaco Canyon Journey September 6-8, 2024

Come join us September 6-8, 2024 to experience the deep stillness and ancient voices of Chaco Canyon. Two night camping with all meals and guiding services provided (see more about the Earth Walks staff below). Time on your own in the Canyon as well.

Chaco Canyon, a major center of ancestral Pueblo culture between 850 and 1250, was a focus for ceremonial, trade and political activity. It is remarkable for its monumental public buildings and distinctive architecture, the most exceptional concentration of pueblos and ancient ruins north of Mexico. Chaco is a great mystery play whose actors are the stars, sun, moon, the land and imagination and spirit of those who  have made their way here over millennia. Both solar and lunar cycles were integrated into the architecture http://www.solsticeproject.org/lunarmark.htm and huge building sites were in alignment with each other over many miles. Great straight roads radiated out from the center of the canyon to distant outlying settlements. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeoastronomy#Chaco_Canyon

have made their way here over millennia. Both solar and lunar cycles were integrated into the architecture http://www.solsticeproject.org/lunarmark.htm and huge building sites were in alignment with each other over many miles. Great straight roads radiated out from the center of the canyon to distant outlying settlements. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeoastronomy#Chaco_Canyon

Many of the Indigenous people of the Southwest consider Chaco as their ancestral home and approach the canyon with the respect that one has for a wise elder in the family. I am one of the countless thousands who feel an inexplicable kinship here as well. Over the more than 30 years of personal visits and leading Earth Walks groups to Chaco, my experiences have been unexpected and surprising, healing and transformational.

Earth Walks support staff, Sharon and Tina Guerrero, have Indigenous historical family roots in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

Earth Walks support staff, Sharon and Tina Guerrero, have Indigenous historical family roots in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

Sharon is a passionate advocate for our natural world as a long-time active member of the Sierra Club and Food and Water Watch. She has been supportive of cultural and social movements in New Mexico for many years working with local, state and federal governments. She is a Curandera and has studied with Michael Harner and Sandra Ingerman with the Institute of Shamanic Studies and sat in ceremony and led ceremony with Native Americans and people from all parts of the world. Having studied with NM Master Gardeners, she is currently coordinating an elementary school garden and teaching outdoor education classes.

Tina was trained as a Santa Fe Master Gardener and is a member and officer of the the Santa Fe Rose Society. She joyfully tends the roses in public gardens in Santa Fe and also volunteers in the Salazar School garden, raising fresh produce for local families. Professionally, Tina served as a fundraiser for universities and organizations, in Santa Fe, NM and across the country, including the National Sierra Club. Most recently, she worked for the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture as staff for the Museum of New Mexico Foundation. She has a degree in journalism, and an early prior background in the news industry.

Come Join Us on the Journey!

Cost: $535 Includes Earth Walks research, preparation and organization as well as guiding services; camping fees at the Canyon; all meals (lunch Friday through breakfast Sunday). Transportation by carpool. For more details contact info@earthwalks.org

HAPPY TRAILS, Doug Conwell

Your Vibe Attracts Your Tribe–the Beat Abides!

In the beginning there was silence. Then came the big beat that some call the bang—intense vibration, energy, rhythm–sustained and steady. Since time began, that cosmic beat has remained through creation, war and turmoil, joy and transformation, chaos and dislocation–an ancient universal messenger keeping memory and hope alive across countless generations and cultures on Earth. And one beat of a drum opened a doorway of awareness for a young man who had just stepped out of the gates of incarceration.

It was 1998 and five of us were sitting around a low table in the little office space on Second Street that was assigned to a Santa Fe, New Mexico community corrections program. Three of the group were on probation from juvenile court. One of us was an Indigenous American woman named Sapokniona, White Feather Grandmother. One of us was me. All had drums in our hands. The faces of the two young men and one young woman on probation look bored or irritated and seemed to say, “OK, let’s get this over.” Sapokniona spoke gently, quietly, with what felt like reassuring confidence.https://sapokniona.wixsite.com/whitefeather

I had been asked to present some of my studies in cross cultural earth related traditions to these youth who were considered “high risk” having had numerous run-ins with the law. But when I got the go ahead, I puzzled about how to offer my experiences and studies to some who might not be remotely interested. I had a Master’s degree in criminal justice, had been a juvenile probation officer, worked part time in a Colorado youth prison and served a year as a counselor in an Army jail where the word “counselor” was an anathema, so I had some reason to wonder about what to present.

In the middle of my muddle came the thought: drums. Drumming was physical and could be energetic and noisy and an attention getter. Local drummer Eric Gent kindly loaned his drums. Eric and his wife Elise had sponsored African dance sessions in Santa Fe for decades. Then I thought of Sapokniona, an acquaintance of Apache heritage who led teaching circles, ceremony, workshops and retreats that included work with veterans’ groups. She kindly agreed to lead the group of youth that day.

“I want each of us to play one single beat, in unison,” Sapokniona said. I was expecting something a lot louder and more physical, but went along with it, as did the others. One beat at a time, like the steady rhythm of a pulsing heart. Each hand with a beater rising then falling on the face of the drum. First softer, then louder, then softer, then it was over. We went around the table to talk about the experience. It came to one young man who looked confused, withdrawn. He hesitated.

Finally, he said, “When I closed my eyes for a while, I saw a bear.”

“Well,” Sapokniona paused, then responded. “My people believe that the bear represents the direction of the west. And you are sitting in that direction. I’m not surprised.” But the rest of us were, including the young man whose face lightened a bit, almost into a smile.

The beat abides—your vibe attracts your tribe.

To my understanding, some Indigenous Americans view the strength of “bear medicine” as the power of introspection. Bear seeks honey, like the sweetness of truth and intuition inside the silent “cave” of mind and soul. Think of Merlin in his crystal cave. In India, the cave symbolizes the creative energy of Brahma which some consider to be the pineal gland located at the base of the brain. https://study.com/academy/lesson/god-brahma-overview-facts-significance.html

As I wrote these words on an early March morning in 2017, the first rays of sun touched my table, the computer, my hands, the photographs of the family “rogue’s gallery” above on the wall. I stopped for a moment to listen to the “sounds of silence” around me: the light twinkle of water in the nearby fountain, the low burbling beating of the humidifier releasing wispy curls of steam, the drone of the refrigerator, the rumbling beat of the attic heater and then…the percussive tapping of typing on the laptop with punctuations, rests, faster and slower rhythms…an opus magnum.

I thought again about the young man in the drum circle who had just stepped through the gates of incarceration. Something happened for him that day that couldn’t be put into words. His eyes got a little wider and there was something like a smile. Maybe the world, too, got just a bit wider with wonder and possibility for him and for all of us in the group, drumming that one beat together.

Did it make a lasting difference in his life in some way? I don’t know. But my thought and hope echo Ann Mortifee’s song, “Just One Voice” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_xixpmvgGY

A single note becomes a song,

A single tree becomes a forest.

A single voice that’s clear and strong

Can turn into a worldwide chorus.

Just one voice, one single voice,

If you say you can, well then you can!

The Native American drum first found its way into my hands in 1982 soon after I arrived in New Mexico. It still does in 2024 after hosting monthly full moon leaderless drum circles in my home for nearly 25 years. In the posts to follow, I’ll share some of my journey with the drum. If you haven’t picked up a drum to try it out, do so! It’s a universal, worldwide instrument. Your vibe will attract your tribe. Have fun!

I Shine Not Burn

“If you leave the journey exactly who you were before you departed, the trip has been much wasted, even if it was just to the Quickie Mart.”–William Least Heat Moon, “Roads to Quoz”

It was a lonely stretch of New Mexico state road where I left the car that late summer day in 1981. Not a cloud in the deep brilliant blue sky. Making my way to the barbed wire fence, with great difficulty I shoved my heavy backpack over, then crawled under the fence onto BLM land. The powerful presence of Bear Mountain loomed above me, but I took a deep breath before I set out to ascend this singular volcanic dome north of Tres Piedras near the Colorado border.

Of all the ethnic family strands, it’s the McKenzie Klan of the Scottish Highlands with whom I feel closest kinship. In the only real picture I have of him, grandpa has a serious countenance and a full white beard that extends to the middle of his chest. I don’t know if he had a sense of humor, but he had a sense of purpose that I like. I imagine him to be a bit dour and highly principled with a sense of responsibility to family and community. He was a decorated Civil War veteran for the Union and a leader. Who knows? Maybe he had a secret life as a fancy dancer! Years ago, my mother gave me his “Gunn’s Family Physician,” a thick tome of the time on health and healing for body mind and spirit. I have traced his hand written notes with my own hand and use the book as a reference for health matters. Just so happens I became a massage therapist and have an ongoing interest in preventive health care. Feels like a lot of Grandpa McKenzie lives on in me.

The first thing I moved into my Santa Fe home where I’ve lived for over 20 years at this writing, was an eight-foot-tall secretary desk grandpa crafted from walnut trees on his farm. He built two large houses mostly by himself, and the desk gives me a sense of continuity, confidence and practical skills, like taking steps up a tall ladder with someone securely holding it in place at the bottom. When refinishing the desk, my father found a picture of Abraham Lincoln, President at the time, pasted onto the desk. Every time I dust that desk, I touch the past and shake hands with my family. One aspect of history not mentioned, though, is that like most places in this country, grandpa’s farm and the trees he fashioned into homes were on Indigenous land that was originally taken by hook or by crook. Whether grandpa ever acknowledged this or offered his respect is lost to history. Even President Lincoln, honored in so many ways, was sadly responsible for the forced removal of Indigenous Americans from their homes and turned a blind eye to horrific treatment of Native people. https://www.history.com/news/abraham-lincoln-native-americans

The path up the 2,000-foot Bear Mountain (called San Antonio on the map) was non-existent. I laboriously traversed up sharp-edged basalt, loose boulders, rubble and vertical terrain. It was slow, arduous going and early on I got tired and frustrated with a heavy pack on my back. Halfway up I noticed a huge black bank of thunderstorm clouds fast approaching from the west. The wind picked up and I started to worry about being caught on the mountainside in rain and lightning. I increased my pace and also increased my level of impatience at the slow going which was much slower than that of the oncoming storm. As the wind whipped more fiercely, I lashed out with the cane at plants and objects “in my way.” Some part of my mind was well aware that I should not be using grandpa’s walking stick in such an angry way.

Finally, I made my way through the scrub oak and Ponderosa pines to Douglas fir and shimmering aspens at the top of the mountain. Quickly making camp and setting up the tent, I waited for the big storm–which never arrived. All that fussing and furious fuming for nothing. It struck me as ironic that our McKenzie Klan emblem, flames shooting from the top of a mountain, mirrored my emotions at the time, because I’d been burning up with impatience on the difficult ascent. Here I was on top of a mountain that millions of years ago was molten red hot, no doubt with flames shooting out in every direction. If I had only remembered the McKenzie Klan motto: “I shine not burn,” (Luceo Non Uro) I might have taken a breath, paused and continued at a more reasonable pace.

I set up the tent and made camp for the night. But later in the darkness I awakened to sounds of footsteps and was frozen with anxiety. It seemed like a two footed being, but I was not sure. Bear? Deer? Cougar? Human? Slowly the footsteps circled the tent with me inside not knowing what the next step might bring. Silently I heaved a sigh of relief as the next steps were away from the tent until I could no longer hear them.

In the morning when I packed to leave, Grandpa McKenzie’s walking stick was nowhere to be found. Could it somehow have been taken out of my hands for misusing it when I was angrily hacking at plants in my way on the furious ascent? Was it the mysterious being in the night that took it away? Whatever. Sadly, and slowly, I loaded up the backpack and walked away from the site for the return home. But then there was a voice in my mind. Where do these things come from in our head, these unbidden words seemingly out of nowhere like a telemarketer on the phone or an unsolicited email? Quièn sabes, but the voice was there, telling me to “Remember to thank the place where you have been!” Following this good advice, I turned around to do so and there, on the ground at my feet–the walking stick! Funny thing though. Years later I discovered that I could have easily driven my car on a gravel road nearly to the top of the mountain. I am glad I didn’t.

Roshi Joan Halifax in her book “The Fruitful Darkness: A Journey Through Buddhist Practice and Tribal Wisdom” (Grove Press; 1st Grove Press Ed edition (March 15, 2004) relates a question she asked of Zentatsu Richard Baker: “Roshi,” she asked, “there is the path to the temple and there is the temple. What is the meaning of the path?” His answer: “Joan, the path IS the temple.” I get that. Without my emotional and physical struggle up Bear Mountain I might not have been given the teaching on the summit. Now, for me the cardinal direction of the north is where I remember my ancestors, especially Grandpa McKenzie. And the teaching? To always thank the people and places I live and visit in life’s journey–my individual earth walk. And another message from the mountain: “to shine not burn.”

Maybe that’s a message trying its best to get through to me all my life. I have this distinct memory from about age six of being in my parents’ basement on Krameria Street in Denver, sitting in the dark and lighting a candle. The memory literally burned itself into my mind when like a moth drawn to the flame my little self-bent forward too closely, staring into the flickering luminosity and singed my eyebrows. Guess I could have singed more than that since my older brother Gary now tells me that his bedroom was in the basement.

As I grew older, the little moth of my mind kept fluttering towards the light, sometimes nearly consumed in the flames. In my hippie days in undergraduate school, we’d usually light a candle as part of the ritual involving the illicit cannabis. One of my close friends during these flights of fancy said she thought lighting a candle was like letting a little bit of God in the room. That stuck, though the use of cannabis did not.

It was the Vietnam War era in the late 1960s and I was feeling schizophrenic. Maybe not clinically, but one day I was dressed in ROTC military uniform, marching on the college playing fields, trying to act like a little soldier. The next day, I was marching in the streets against the war. What was wrong with this picture? Then came officers’ basic summer camp in 1970 at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma. At the beginning of training, we were warned repeatedly, “Don’t touch the barrel of the weapon you have been using. It will burn your hand.” Good advice, but what I call my “angel guides” had me do exactly that, so I did indeed burn my hand severely and couldn’t train with a weapon for a while. Another one of those unbidden messages telling me to seriously consider what the heck I was doing.

I actually don’t remember much else about summer camp, probably because I want to blot out that distressing time in my life. My senior year in college I went through agonizing soul searching, counseling, lots of lit candles, the news about National Guard killing of anti-war student protesters at Kent State University in Ohio and the My Lai massacre of Vietnamese civilians by US soldiers. My final decision was to “shine and not burn” in this terribly wrong military conflict. I applied successfully for noncombatant status, which meant I was denied the officer’s commission and subjected to the draft. Ultimately, I was drafted and served two years in the Medical Service Corps, facing some hellish situations. But that’s another story.

In later years I discovered the teachings of a wise East Indian avatar, Paramahansa Yogananda. In a book called “Man’s Eternal Quest” he wrote:

In later years I discovered the teachings of a wise East Indian avatar, Paramahansa Yogananda. In a book called “Man’s Eternal Quest” he wrote:

…You cannot make steel until you have made the iron white-hot in the fire. It is not meant for harm. Troubles and disease have a lesson for us. Our painful experiences are not meant to destroy us, but to burn out our dross, to hurry us back Home. No one is more anxious for our release than God.

After the Army I headed back to my hometown of Denver, Colorado. But fire seemed to follow me wherever I went, or maybe I followed it. One surprise birthday party at a friend’s home, I got the call that the fire department was scraping the remains out the window of my rental home in the Cherry Creek area. Faulty wiring had shorted out an electric blanket on my bed. One good thing about the fire though: the gold polyester wide lapel leisure suit my parents had given me melted. I never did like that goofy looking thing.

Work and graduate studies at the University of Colorado took me to Boulder. That went pretty well but the green bubble of Boulder was surrounded by the front range “brown cloud” air pollution in the Denver area. It was a dry summer and thick smoke from fires in the foothills added to the poor air quality. I thought I had returned to my hometown after the Army, but it had been swallowed up by rampant urban growth we humorously called “Californication.” I felt pushed out of the area, but I also felt a pull to New Mexico.

So, Mona my cat and I packed up and moved to Santa Fe in 1978 and after several years found a wonderful old crumbling adobe duplex rental on Upper Canyon Road that at one time had been in the hands of the first Santa Fe Archbishop, a Frenchman named Lamy. But unwelcome fire continued to follow me. One day I came home to find the foam rubber plug to my fireplace melted and a large pillow sitting in front of it on slow burn, headed to the 150-year-old wooden plank floor. Years later when I was teaching my “Earth Walks: The Spirit of Place” class at Ghost Ranch Education and Retreat Center north of Santa Fe, I came into my classroom to find the fireplace mantel smoldering, somehow lit from my incense sticks. Hmmmmm….was there a pattern going on here? Burning, not shining like the McKenzie Klan motto advises.

It wasn’t all hell fire and brimstone, though. Along the way I started picking up clues to fire being a way to burn out my “dross” and help me hurry back “home.” Sunday night fires in the Ben Franklin stove had been a family tradition growing up, along with popcorn and hot chocolate, us boys polishing shoes for the school week ahead and watching our favorite TV shows–Gary Moore, I’ve Got a Secret, Gunsmoke and Bonanza, To Tell the Truth, the Carol Burnett Show…and all the rest.

Now in New Mexico, Sunday nights have become my own tradition. Popcorn and hot chocolate for sure, but no more shoe polishing. The longer I lived in Santa Fe the more I found fire to be an essential element of my consciousness. The McKenzie Klan symbol is “fire on the mountain,” but there haven’t been volcanoes in Scotland for millions of years. Near Santa Fe, however, is a recently active region of big-time eruptions and magma flows. The largest man made “fire”–the atomic bomb–was developed just 30 miles away and tested in the southern part of the state. Talk about the need to “shine, not burn!”

Along the way in Santa Fe, I met Concha Garcia Allen, elder member of the Mexican Danza Azteca ceremonial prayer group. She introduced me to “Tatewari” or Grandfather Fire in the native Huichol tradition. Tatewari represents–actually becomes–a breathing, speaking elemental force which empowers a person to follow her heart path to completion. For me this age-old shamanic practice made complete sense as I began to weave the threads of my own Scottish highland Fire Klan heritage. On Earth Walk journeys in Canyon de Chelly, Dinè guide Daniel also spoke with Tatewari, although by another name, in the embers of our campfire divining meaning and messages for those willing to listen.

Danza Azteca ceremonial prayer group. She introduced me to “Tatewari” or Grandfather Fire in the native Huichol tradition. Tatewari represents–actually becomes–a breathing, speaking elemental force which empowers a person to follow her heart path to completion. For me this age-old shamanic practice made complete sense as I began to weave the threads of my own Scottish highland Fire Klan heritage. On Earth Walk journeys in Canyon de Chelly, Dinè guide Daniel also spoke with Tatewari, although by another name, in the embers of our campfire divining meaning and messages for those willing to listen.

In 1993 leading a small group of people to Oaxaca, Mexico for Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) I discovered the ancient Mexican god of the fire and brought a weaving of the image back home where it hangs above my bed in all its fiery composure. That same year I traveled to the home of Annie Kahn, Dinè elder and teacher, for a visit and sweat lodge. Sadly, the lodge had been burned down by arsonists just prior to our arrival. Annie sent family members into the nearby mountains to gather the proper plant materials to do ceremony and prayer. As soon as possible, we all pitched in to help rebuild the sweat. This, Annie said, was essential.

“Never let something bad happen without making it right as soon as you can,” she explained. “Don’t let the bad thing fester.” That was good advice to me who tends to perseverate and stew over sometimes the smallest things.

Ten years later in 2005 and half a world away, I was floating in a boat on the sacred Ganges River fascinated by flames of the Indian Hindu “Aarti” ceremony. It was night and the waters of the great river in front of us reflected and intensified what we saw on the shore. Brahman priests clad in saffron colored robes chanted continuously, circling multi-tiered butter lamps in great arcs around their heads, ringing bells and chimes and intoning ancient prayers. It had been this way for centuries and though my traveling companions and I were tourists, the power of the ceremony was anciently familiar in my Scottish Fire Klan bones.

This was not the only flame I saw while in India. Days later our group visited Bodh Gaya, the site where it is said that Siddhartha Gautama, the spiritual teacher who later became known as the Buddha, is said to have attained enlightenment. An offshoot of the original venerable “peepal” or fig tree under which he attained this state of consciousness now grows next to the large temple erected in his honor. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bodhi_Tree

As I knelt at the steps in front of the tree and bowed to honor the Buddha, my head bonked on the stones so hard that I thought it must have been audible to those around me. Immediately amidst the ringing in my ears I heard in a loud exclamation: “Awaken!” Funny thing, one of our tour leaders, Annette, told me later she had the same exact experience. I wonder what spiritual Youtube channel we both were plugged into?

Returning to the scene of the head bonk that evening, thousands of pilgrims were circumnavigating the temple, prostrating themselves on the sidewalk every few feet. Over the loudspeakers a continuous droning chant was taking place. But I found the low bass tones irritating and was hoping the group of younger monks in front of me were next in line to chant, hopefully with a more baritone. I sat opposite the group, taking it all in—the crush of the crowd, the droning basses, the intense spiritual fervor and me, just sitting there quietly watching. For a moment there was a parting of the crowd and gazing across at the seated group of monks, I was astonished at what I saw: a large flame inexplicably suspended in midair above them. The crowd crushed in again, then again briefly parted. The flame was gone.

But not gone from my consciousness. The flame was as real as the nose on my face and blazed its image into my mind. I had to find out what it meant. Once back in New Mexico, my search uncovered a rich and complex symbolism for the flame across cultures and traditions. The Christian view sums it up for me: the Holy Spirit. Kinda gives a new light–so to speak–on popcorn, hot chocolate and my Sunday night winter fires. I keep lighting those fires and also lighting a single candle each evening that glows throughout the night. It’s a way to remember the message of Bear Mountain and the counsel of my McKenzie Klan to “shine not burn” as I continue on my earth walk this lifetime. (For worldwide meaning of the sacred flame: https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/fire-symbolism-flames-ignite-faiths-and-inspire-minds-004404 From this website, the following picture.)

Grandmother Spider’s Web

We are the weavers, we are the web

We are the flow, we are the ebb

—Shekkinah Mountainwater

She hid herself as quickly as she could. The hulking figure was walking directly towards her and she knew what had happened to so many others of her family in a similar situation–a horrible death. Crouching in the shadows she waited for what was to come next. But in her wildest imagination, she could not have guessed what did come next.

“It’s OK, I’m not going to hurt you. You can come out,” I said quietly as I gently knocked on the window frame where the spider had hidden when she saw me walking towards her.

To tell the truth, I was lonely. Coming from a middle-class family, I was finding it hard to relate to the uber wealthy students at the University of Denver where I attended in 1971. They stepped out of their Lamborghinis with designer jeans that cost more due to the intentional holes in the knees. I stepped down from a used VW bus to get to my clerical work study job at the history department office.

This particular night in my basement apartment I felt especially lonely. When I spied a spider on the wall near the window, I thought, “Maybe here’s someone I can talk with.”

Little did I know how right I was.

As I walked towards the spider, she saw me too and quickly retreated under the window frame, fearing the worst. Many people smash spiders when they are in their home, maybe out of fear of the unfamiliar, unknown—the “other.” With some, their fear gets out of hand and they feel uneasy in any area they believe could harbor spiders or might have a web. Some people scream, cry, have emotional outbursts, experience trouble breathing or go into panic attacks. We’re talking extreme arachnophobia, and in some cases, even a realistic picture or drawing of a spider can trigger intense anxiety.

“It’s OK, I’m not going to hurt you,” I repeated to my little hidden arachnid.

Well, if I haven’t lost you at this point, perhaps you’ll believe what happened next: First one little leg emerged, then another and another until she was fully out on the wall. “Hungry,” came to my mind. I searched the nearly empty college student fridge, brought back yoghurt and put a drop of it on the wall—which the spider moved up to and ate. A few days later, she traveled on.

I traveled on, too, was drafted out of graduate school into the Army during the latter days of the Vietnam War, went back to Denver after my discharge, entered graduate school at the University of Colorado and eventually moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico from Boulder. One day, in 1980 in the Chupadero Valley north of Santa Fe where I was living, I felt I was being watched while showering. Looking up, I noticed a black spider had come out of the plumbing. I wasn’t too concerned as she was busy working on her web and enjoying a bit of steam bath at the same time. This went on for months until spring solstice 1981 when I sadly found her lifeless body belly up on the shower floor. And as I suspected, there was an orange hourglass on that belly. A Black Widow spider.

Spiders kept showing up around me. In 1984 at the Hopi Mesas of Arizona I was helping guide a tour for the Wheelwright Museum of Santa Fe as the new director of public information. Waiting for the tour group to assemble after breakfast one cold and breezy morning, I took a short walk to the edge of the mesa. Here I was 300 feet above the desert floor on a dry wind-swept mesa but from somewhere I heard a small drip of water. I gazed out at the valley below and the sacred San Francisco peaks in the distance. It was a profound moment that I expressed in these words, called “Over the Hill”:

Insistently,

the wind pushed me

over the rock ledge

and down to the lair of Grandmother Spider

Water dripped like

grains of sand,

like time itself into

the pool of time again.

Here, where sky meets

earth,

Man met something

not quite understood.

In the mystery,

in the majesty,

where stones speak

words unutterable,

A breath,

a new beginning,

a step into the unknown.

“You’ve been over the hill,”

He said, his suglassed

eyes narrowing in scope,

wide with knowing.

“Yes,” I said.

“I have.”

As the museum tour progressed, I noticed homes with a black spider painted over doors and later learned about Grandmother Spider who stories say wove the web of Creation for First Man and First Woman. I learned that some Indigenous Americans thought the spider protected against danger from natural phenomena.

In Hindu mythology, the little arachnid represented the weaver of magic and destiny. Egyptians saw her as an attribute of Neith, a creator of the world and to the Romans she was as omen of good luck. But when it came to Christianity, both spider and snake didn’t fare so well, as they represented the Devil ensnaring sinners. No matter the view, it was a lot of responsibility for such a small creature.

Small but powerful. Spider silk is stronger than steel and tougher than Kevlar pound for pound. Their web is one of the most dramatic examples of perfect geometry in the natural world and such a successful invention that it has remained essentially unchanged for 140 million years. Recent research has shown that the webs actually strengthen after they are slightly damaged. According to scientists, spiders are antisocial arachnids who want to be left alone. Maybe so, but the spiders I kept meeting were friendly, even helpful.

In May 1986, I found myself resting upon a pink granite boulder above the Randall Davey Audubon Center in the upper Santa Fe canyon area. I was quiet, enjoying a meditative moment. As I looked down at the trickle of water flowing below, I saw something next to it that looked like a stone, but not quite. Curious, I climbed off the boulder for a closer look and discovered it was a weathered turtle shell. What are the chances of that in this area I wondered to myself. As I approached, spiders on either side of the shell seem to be guarding it, even offering it to me. They withdrew as I got closer. Astonished at what was happening, I accepted the shell as a gift and later it became the receptacle for the pennies I use with the Chinese I Ching system of divination.

Grandmother Spider kept weaving my story web ever larger. Nearly 20 years later in February 1997, I was fortunate to witness the Snake Ceremonies at Hopi Second Mesa. I also visited the home and studio of artist Ross Joseyesva Jr. who had served as a guide for an Institute of Noetic Sciences group I led in the Southwest a number of years before.

I was seeking a new watch band made by a local Southwestern artist, and I stopped in to say hello and see Ross’ jewelry work. After a pleasant catch-up conversation, we went to the studio and looked through his portfolio. As he turned a page, I spotted a design with spider.

“That’s the one,” I exclaimed, and began to relate my spider tales. He listened quietly and then said, “You are a friend of the spider. I’ll put the friendship sign on the design.” It just so happened that Ross’ studio was within sight of a shrine for the Spider Klan. I ordered the watchband without making a deposit or pre-payment.

Weeks went by and the watch band went to the back of my mind as I got busy planning an Earth Walks overnight event at the home and weaving studio of Max Cordova in the Truchas foothills above Chimayo north of Santa Fe. The Cordova studio and residence sits on a spectacular finger of high-country land overlooking the village of Cordova and a wide circle of sky, mountain ranges and the Rio Grande Valley.

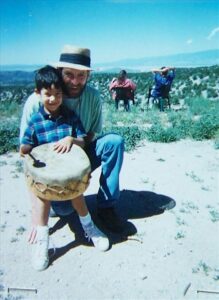

It was summer solstice, June 21, 1997 and full moon, an auspicious convergence. Participants included Max and his family, 77-year-old curandera (healer) May Delgado and other elders from the area who dropped by to visit as well as a five-year-old boy named James who was wise beyond his years. And it seemed to me that Grandmother Spider showed up as well.

As the group gathered, little James stood tall atop a green plastic chair facing the immensity of desert and mountains to the west. In his hands, stones were speaking through him to us, this weekend gathering of our Earth Walks vecinos–compadres y comadres, tios y tias–friends and family new and old.

James held a small stone in his young hands. “Now pass this stone from person to person,” James instructed. Stone passed, hearts opened, the breeze blew and the earth turned a bit more in its dance on this our second Earth Walks for people living with HIV, their care givers, friends and family. We camped out on the land, full moon sailing silently over the majestic Truchas peaks, some still white with winter snow, silently standing sentinel above us.

“Just do the weaving and don’t think about it much,” Max advised, when the next day we all tried our hand at his looms, looms that over the years had created an abundance of beautiful tapestries. As I began to run the shuttle, mental distractions and random thoughts cris-crossed my mind. My shuttle got tangled in the threads like a fly in a web, and like the fly, my mind got tangled up too.

“Just keep it simple,” I told myself as I finally extracted the shuttle from the threads. This was a lot like other times in my life, trying to do too much in too little time. It seemed as if Grandmother Spider was telling me to slow down, have some patience and get my conscious mind out of the way of the creation. And I did. At least a little, enough to see some of what Max was talking about.

It didn’t dawn on me until 2017 while writing this story that there was an amazing pattern weaving itself all around me during the Earth Walks, like a spider web of balance and beauty. Just the day before our visit to the weaving studio in Truchas, my spider watch band arrived in the mail from Ross. Fortuitous timing, on a full moon summer solstice. I hadn’t made any payment to Ross. He simply sent it when it was finished in an act of trust and friendship.

That act of trust spiraled back 40 years to the trust a spider at the window and I had one lonely night during graduate school. All my web of relationships with spiders over the years has woven sacred strands of kinship between me and the natural world. I know now without a doubt if I get into a basement of loneliness again, I’ll be sure to have yoghurt on hand and look for one of God’s little eight-legged children.

Chaco Canyon, New Mexico: “Tasting Forever”

Early morning, November 11, 1980 and the Chaco Canyon visitors’ center was not yet open. I sat in my car waiting. And watching. Watching a meditation in movement unfold in front of me on my first visit–more like a pilgrimage–to Chaco Canyon National Historical Park. A man was slowly, methodically and silently sweeping the entrance sidewalk, starting from one side and carefully making his way to the other. Not with a store-bought broom, but rather one that was handmade from brush and plants gathered in the area. Unlike me, the man was not in a hurry. He was slightly leaning, intent on each sweep of the broom, each passage down the sidewalk like a reverent monk at a Buddhist temple. There was no one else but us around in the silence save for we two and the early morning birds, unseen insects and other life forms waking up to the day. Deep breath, palms together, I bowed as Chaco greeted me, conveying a message and an image that I would carry with me with on numerous visits in the coming decades.

Chaco Canyon, a major center of ancestral Pueblo culture between 850 and 1250, was a focus for ceremonial, trade and political activity. It is remarkable for its monumental public buildings and distinctive architecture, the most exceptional concentration of pueblos and ancient ruins north of Mexico. Chaco is a great mystery play whose actors are the stars, sun, moon, the land and imagination and spirit of those who  have made their way here over millennia. Both solar and lunar cycles were integrated into the architecture http://www.solsticeproject.org/lunarmark.htm and huge building sites were in alignment with each other over many miles. Great straight roads radiated out from the center of the canyon to distant outlying settlements. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeoastronomy#Chaco_Canyon

have made their way here over millennia. Both solar and lunar cycles were integrated into the architecture http://www.solsticeproject.org/lunarmark.htm and huge building sites were in alignment with each other over many miles. Great straight roads radiated out from the center of the canyon to distant outlying settlements. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeoastronomy#Chaco_Canyon

Many of the Indigenous people who guide Earth Walks groups consider Chaco as their ancestral home and approach the canyon with the respect that one has for a wise elder in the family. I am one of the countless thousands who feel an inexplicable kinship here as well. Over the more than 30 years of personal visits and leading Earth Walks groups to Chaco, my experiences have been unexpected and surprising, healing and transformational. I share some of these in the experiences that follow.

——————————-

August 15, 1986: I walked alone on a mesa ledge in Chaco Canyon 300 feet above the huge pueblo complex called Pueblo Bonito. To get here wasn’t easy: a long winding trail from the parking area below, then a climb up a steep and narrow trail up through a slit in the sandstone mesa and still more walking. It took time and lots of effort but I needed to get up and out to view the vast open expanse of land and sky for inspiration and a break from my recurrent anxieties about income and loneliness. Those issues were oddly alternating with a deep feeling of abundance and contentment, issues I found reflected in this Chaco environment of sparse water, harsh climate and immense inspiration.

The winds of the canyon were just a gentle zephyr during my walk. Birds chirped from the cliffs around me. I heard my footfall step by step on the bare sandstone trail amidst the quiet of the canyon. I was walking a trail used hundreds of years ago by thousands of ancestral Pueblo people coming to this Center Place of the Chaco world. They traveled on constructed roads that radiated out in all directions, traversing a landscape barren of trees and water. The roads were wide and straight like highways leading sometimes to an identifiable goal, sometimes not. Huge earthen ramps were constructed when the road met a steep cliff.

I was not thinking about much, just enjoying the walk when the unexpected occurred. My long-deceased cousin Janis Hammer appeared in my mind. I had not thought much about her in recent years, even though she and I were the same age and were inseparable playmates. I didn’t have a sister and she was an only child so when we were together, which was often, we had wonderful fun. Janis died instantly in a car accident in which my brother was driving in El Paso. My brother was not at fault, and he almost died also because of the accident. I was deeply stunned at her loss and refused, as I recalled, to get out of the car to attend graveside services. I remembered sitting in my parents’ home after Janis’ death, not speaking, not crying, just being silent. Perhaps I never mourned her loss, not wanting to feel the pain of loss of someone so dear. Perhaps as a teenager I did not know how to grieve.

years later, in the remote desert of Chaco Canyon, Janis as a woman my own age came into clear inner view. Tears welled up in my eyes as I realized I indeed had never accepted her death. Overcome with emotion, I stopped walking, and turned to face an opening across the canyon called the South Gap. Through the space between the canyon walls, I could see an almost limitless horizon. And in the midst of the morning, surrounded by the unseen ancient ones of this place as witnesses and guides, I released Janis and her spirit to go where it needed to go. And I was freed as well to walk my path with my load a little lighter.It was only later I learned that archaeologists discovered a huge mound of broken pottery on the north facing side of the site called Pueblo Alto where I walked. They speculated that Pueblo pilgrims would travel a long arduous journey across the dry desert land, ritually breaking their potteries perhaps as a symbol of releasing not just physical burdens but inner ones as well. On this day of arrival at Chaco, I joined with those ancient ones and did the same.

——————————————————————-

“Tasting Forever” with Thanks to Simon Ortiz

September 23, 1991: During my twelve years of living in New Mexico at the time, Chaco Canyon had drawn me like a magnet. I felt a sense of mystery, wonder and timelessness just in just hearing the name for the first time. On this day I was at Chaco to join friend Charles Bensinger and Guatemalan spiritual leader Don Alejandro in a prayer ceremony to observe a fall equinox phenomena interplay between the sun and ancient manmade structures.

But darn it! I had a persistent pain in my stomach that began even before I arrived at Chaco. Was the pain physical, emotional or both? It had been a difficult year on many levels. In January President George Bush declared war on Iraq. Iraqi leader Sadam Hussein deliberately set oil wells on fire in the Persian Gulf creating a huge environmental disaster. In the Soviet Union, repression rose after a hopeful year of incipient democracy. The U.S. economy was in serious trouble. On the personal side, a close relative entered a hospital psychiatric ward, plagued with inner demons of doubt, paranoia and depression. A romantic relationship I was in for several years ended. The biggest blow was the death of my mother. Maybe coming to the canyon today was not only to attend the equinox ceremony but to find solace and some relief from the stomach pain as well as the pains of this world.

I drove here alone, something that always helped me unwind from my daily routines, responsibilities and anxieties at home. Turning off the well paved U.S. Highway 550 was a step in slowing down because the next 13 miles were rough and narrow, some of it impassable if wet. The windswept landscape was bone dry, with only sparse  sagebrush, cactus and occasional juniper trees dotting the horizon. Yet this was the desert environment I had lived in most of my life that made me conscious in a way a more lush, wet world did not. The sound of a single bird singing, a drop of rain or trickle of water, the flash and wiggle of a lizard tail–here in the desert they reminded me not to take life for granted–all my thoughts and actions were consequential.

sagebrush, cactus and occasional juniper trees dotting the horizon. Yet this was the desert environment I had lived in most of my life that made me conscious in a way a more lush, wet world did not. The sound of a single bird singing, a drop of rain or trickle of water, the flash and wiggle of a lizard tail–here in the desert they reminded me not to take life for granted–all my thoughts and actions were consequential.

At the campground I set up tent and gear, checked in at the visitor center and headed out into the canyon for a first walkabout, which I decided would be the high mesa ledge overlooking the massive ancient site of Pueblo Bonito. Getting there involved a long walk and a tricky climb 150 feet up through a narrow slit in the sandstone walls. All the while, there was a persistent and painfully persistent jabbing in my stomach. Pain or no pain, though, I was not going to miss out on this time in Chaco.

I clawed my way up and onto the mesa ledge and emerged onto the sandstone ledge like a newborn baby who has struggled his way out through the birth canal. It was afternoon and the light was as mild as the temperature. From the ledge I could see much of the canyon below and miles in the distance beyond.  The mesa ravines supported wiry bunch grass, cliff roses wafting an occasional sweet fragrance, an array of desert wild flowers and Apache plumes now fluffy with seed pods illuminated like bright lights in the late afternoon light. Rocky erosional pathways were exposed like large veins in a human hand. Mysterious circular holes in the sandstone ledge looked human made and left me wondering about who, what and when.

The mesa ravines supported wiry bunch grass, cliff roses wafting an occasional sweet fragrance, an array of desert wild flowers and Apache plumes now fluffy with seed pods illuminated like bright lights in the late afternoon light. Rocky erosional pathways were exposed like large veins in a human hand. Mysterious circular holes in the sandstone ledge looked human made and left me wondering about who, what and when.

This was the path of the ancients I trod, the route so many walked by foot for hundreds of miles to the Center Place, this canyon where thousands of rooms in ancient pueblo buildings had been carefully constructed in alignment with heavenly cycles of sun, moon and stars. I wondered if I was part of an ongoing drama, coming here to help find my own center place to ground myself in my daily life. There was a digital world wide web where I spent many waking hours connecting to others electronically, but where was that center place where I could rest and find relief in the sacredness of the everyday? Chaco Canyon had been one such physical place for me over the years, a place of vast silence that evoked in me a sense of the awesome interconnectedness of all.

As I walked, breathing in the morning silence, I noticed a bit of crumbling red sandstone on the trail, and wondered if it might have served as paint for the exquisite Chaco pottery made hundreds of years ago. Kneeling down, I wet it with saliva on my index finger to determine the color and texture; then without thinking, licked the red earth again, like licking the sweet batter on my mother’s spatula at home when she was baking a cake. It was rough, sandy and not at all like cake batter. But for some inexplicable reason I repeated the procedure. More licks of the earth batter. Within minutes, my stomach pain vanished. How? Why? I had no explanation, but a poet once said, “Sometimes the most important thing is the most inarticulate.”

Native American Acoma Pueblo poet Simon Ortiz, expresses it this way in his poem “Canyon de Chelly”: https://lecuona.weebly.com/uploads/5/9/1/1/59118557/mi_madre_canyon_de_chelly.pdf

Lie on your back on stone

The stone carved to fit

The shape of yourself.

My son is near me.

He sits and turns on his butt

and crawls over to stones,

picks one up and holds it,

and then puts it in his mouth.

The taste of stone.

What is it but stone,

the earth in your mouth.

You, son, are tasting forever.

At that moment I became part of the place and was given a gift from the canyon. That night, another gift: I drifted to sleep to the sound of drumming and chants nearby in the campground. Then a dream: I watched a man (was it me?) ceremonially offer cornmeal to people gathered in a circle, inviting them to volunteer their service in some way. I awoke during the night just as a waning moon rose above canyon walls–orange-gold, beautiful, complete silence in the campground. Later that night I drowsily awakened again under a blanket of infinite stars and watched a meteor trail across the vast canopy. I thought: “This is why I come to Chaco. To reconnect with my home in the stars.” Then, an even larger meteor blazes across the darkness, as if to answer, “yes.”

After breakfast, I joined Guatemalan elder Don Alejandro for teachings on that fall equinox day. His words of wisdom still ring in my heart, as true to me today as they were then: What are you doing here? Why am I here? Each one of us, we travel to different parts of the world. But what are we looking for? We are looking for love and understanding among all beings that inhabit the Earth. We are searching for something in our minds for what we can do to defend Mother Earth.”

——————————————————————————-

May 23, 2007: I sat and shed tears of sorrow, shame…for what I was not sure. I was working for the Santa Fe Public Schools as the emergency management and crisis response director and for the second year in a row had applied to the U.S. Department of Education for a large grant to bring our schools up to national standards. I knew it was well written and worthy of funding….and I also knew I failed to include a required sheet of paper that could result in rejection. It was too late to add the missing paper and I had to mail the proposal. I felt I had let down the schools, my community, state, the world! Maybe this was not the work I should be doing, I agonized. And yet, as I drove from the post office in abject sorrow, I prayed: I need, and this application needs, a miracle to survive the heartless, objective “bean counters” at the federal level. Just at that moment a CD in my car that had been stuck for days in the player began to play. The speaker on the recording was saying that ALL of us make mistakes and God loves us no matter what our mistakes. I took it as a sign that perhaps a miracle could happen for the grant application. But–and a big but it was–I was still ashamed of my oversight of the missing piece of paper and was not forgiving myself.

Two days later I arrived at Chaco Canyon to a spectacular technicolor sunset. I was on a solo trip planned weeks before, but I didn’t know then how much I would need this time alone. Others wanted to come but no one could. Perhaps I was supposed to be here on my own to find some peace and comfort from the grant application ordeal.

The first morning I climbed the trail to a mesa above the campground for a sunrise meditation and read the words of East Indian spiritual leader Paramahansa Yogananda from an article entitled “Ridding Yourself of Worries:” “Worry takes time and energy. Use your mind instead to make some positive effort…every time you worry you put on a mental brake and in struggling against that resistance you place a strain on your heart and mind…remember there is someone on this earth suffering 100 times more than you are…if you do your best, God will reach down his hand to help you….” Good advice, but my mind still had the brakes on, preoccupied with the grant application.

Late afternoon I headed out for a walk from the monumental kiva (underground ceremonial structure) of Casa Rinconada on the south side of the canyon. At this site almost 20 years ago I experienced the awesome mystery of Chaco. I was guiding a group from the Institute of Noetic Sciences and though it had begun to snow, many of us happily hopped off the van and up the trail to Casa Rinconada. We were able to sit inside the huge kiva on low lying walls rimming the circular structure and take a few moments of quiet, despite the swirling snowflakes and chilling wind. My eyes were closed in meditation when something inexplicable occurred. First, my inner vision filled with a bright golden light. Then I felt a warm glow flow within and around me. As soon as it came, it left and I opened my eyes and led the group back to the waiting van.That night the others who had sat in the kiva shared that they too had the same experience as I did. Just a fluke occurrence? A collective delusion? Casa Rinconada was for hundreds of years was likely filled with prayers for rain and sustenance. Community gatherings offered songs to thank the gods for corn and crops. As it seems today in Pueblo life, prayers probably invoked the guiding presence of unseen spirits. Chaco is a thief of time, a place that marks the passage of time in its celestial architectural alignments and a place where all of time is present in the moment. I believe that our group was in the inexplicable presence of the ancient ones in that kiva “snowbowl,” an invisible presence that could not be spoken, paraphrased or translated into any language. In “The Little Prince,” St. Exupery said it this way: “What is invisible to the eye is truly important. It is with the heart that we truly see.”

It was from this great kiva where I began my solitary walk this late spring afternoon. At least two major roads perhaps a thousand years old connect to the site from places many miles distant. The little trail I followed went around the mesa through a large opening called the South Gap. It was just me and the raucous ravens, an occasional scuttling lizard and the wind whipping itself into a drumbeat in my ears. I gathered a few fresh spring sagebrush branches to make prayer bundles for friends, and inhaled a deep awakening breath of the fresh pungent aroma. At the mesa I ascended a zig zag trail up the side. I had been here before, but this time the going was slower, the trail up seemed steeper. I was carrying more than my little day pack. I carried an emotional burden of shame and sorrow from the woes of my grant application.

Eventually I was on top of the mesa, a windswept sandstone saddle. It was a stunning view to western horizon–perhaps thousands of acres of red-orange globe mallow plants in bloom, glowing brightly from late afternoon sunlight like a red ocean with an interplay of light and clouds–grey, blues, whites amidst the rest of the spring green landscape. The panorama was vast, bordered by the Chuska and Lukachukai Mountains 50 miles to the west. As I gazed quietly at the oceanic desert spectacle, a dream from long ago came back to me: In the dream I was standing cliffside by the ocean as a truly wise person next to me motioned with his arm sweeping from one side of the horizon to the other, saying, “THIS is who you TRULY are!” Now at this moment in this reality, from the heart of Chaco to my own heart, I heard within myself these words:

“You are NOT a piece of paper nor a job description, not a human doing. You are a human becoming, perfect in his imperfection!”

Awestruck, I backed away up the mesa from one step at a time, keeping the view to the west in a solid gaze. Up the trail, over rocks, ledges, tree roots one step at a time, backwards. Then awe became celebration as I cried in joy, hopped, skipped and jumped realizing that the self-imposed burden of my week’s disappointment regarding the grant application had been lifted. I realized that the grant application was just the apparent source of my distress. Down deeper it was internal issues of feeling “I am not enough” or “I should be doing better.” But “better” was never enough. Now, thanks to the “spirit of place” and Chaco Canyon, I knew that no matter the outcome of the grant, I was heading home, a “human becoming” more whole and happier.

The application was not approved. But the next year, on my third try, we secured $250,000 to do the much-needed emergency preparedness work for Santa Fe Public Schools.

—————————————————

August 10, 2012: I was on another personal retreat at Chaco Canyon. I tried to come in June, but was stopped in my tracks when my home was broken into. That day I returned home to pack up and leave for the trip. Entering the house, I saw the patio door curtains blowing a bit in the breeze and thought, “I left the door open while I was away on errands.” Then I saw the shattered shards of glass and the large rock hurled through the double pane door scattered on the floor. My plans for Chaco were shattered as well. It took over a week and hundreds of dollars to get a new glass door from the Colorado manufacturer.

That whole year had been a tough time personally and also in my community and the nation. Just like the rising hot temperatures, burglary rates were skyrocketing in Santa Fe. Fires raged throughout the western U.S. and Denver set record high temperatures. A fire near Colorado Springs consumed over 300 homes. The mid-Atlantic states sweltered under a record breaking 104 degrees and Washington, D.C. declared a state of emergency due to huge damaging winds. Close to home, my kitty companion of nearly 20 years was not eating much and was uncharacteristically staying outdoors a good deal of the time. It was possible that she had a failing kidney.

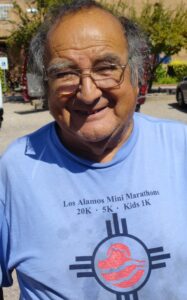

So, this solo sojourn to Chaco was a needed retreat. I started the day at Socorro Herrera’s Cafe in Medanales north of Espanola, enjoying breakfast with Tio Manzanares. Tio and my path crossed at Ghost Ranch Presbyterian Conference Center in the early 1990’s where I was teaching a retreat called “Earth Walks: The Spirit of Place.” He was giving talks to Elder Hostel groups, mostly about his time working for 12 years as a young man for artist Georgia O’Keefe. At a meal together in the Ghost Ranch dining hall, I quickly learned that he had much more to share than just his tales with the famous “Miss O’Keefe” as he called her. His stories of artists, aliens and angels left me alternately spellbound, skeptical or rolling in laughter but always I felt the good-hearted nature of this man who had spent most of his life in the Abiquiu area north of Santa Fe.

It was hard work, but for much of his life Tio was a stone mason, building walls and other structures in the nearby villages. That meant collecting lots of stones–8.900 truckloads to be exact, wearing out 42 trucks over the years from 1972-1994, he said. Seems like he had collected as many stories as stones, but he was given some advice about stone collecting that could well apply to storytelling.

“An Indian friend told me that some of the stones were not supposed to move from their spot,” Tio shared. “First I thought a rock doesn’t have any understanding. Then sometimes my truck would break down for some reason. Once I caught on and figured out that those stones were not intended to move, I didn’t have a problem. And the rocks were gentler to me. I didn’t smash my fingers as often and I could move the stones more easily.”

On one occasion his truck did break down on a late winter afternoon in an isolated arroyo where he’d been traveling. Light was fading and so was the temperature. It was far from home and Tio was worried about what to do. For a minute, he thought he heard sounds of a car. Climbing the hill above he saw headlights heading towards him. The car shortly arrived and a man stepped out, asking if Tio needed help.

“Who are you? Where did you come from?” asked Tio, totally mystified at the stranger who appeared seemingly out of nowhere.

“I’m just helping out people who get stranded,” he replied. “And I’m from a place you wouldn’t even know about.” With that, the man went to his car and pulled out the exact tools and parts needed to fix Tio’s truck, parts that would have required a trip into town to purchase.

“Maybe that stranger who helped me on the road was Saint Jude,” Tio mused. Towards the end of his stonemason career, Tio smashed his hand severely and he cried out to Saint Jude in pain, “If you think you can change my life, do it!” Saint Jude is the patron of hopeless causes and despair. In a week Tio had a new job and quit the stone mason business. Ever after, he kept a lighted candle at the foot of his Saint Jude statue. In any case, after the truck was repaired, the man got into his car, backed up, turned around and left. Tio quickly climbed the small hill again to watch him leave…but there was no sign nor sound of a car in any direction.

Tio and I were about done with the breakfast of good and hot New Mexico huevos rancheros (spicy red and green chili–I always ask for “Christmas”) when Socorro, who managed the cafe stopped by with the check and a smile. She and Tio were mariachi singers and musicians “back in the day,” and it was a delight to see them recount those times. Tio said she was an award-winning diva of northern New Mexico songs. Socorro had her own stories to tell, some of them filled with the flutter of angels’ wings and miracles.

One day she was in the cafe early, preparing a huge catered meal order. It was just her alone, without staff help that day, and the clock was ticking. This was a big deal order, which could lead to much more needed business. But how was she to get it all done in time? The answer to that was doing the thing she knew best: prayer. She walked to the wall where an image of her patron Saint Socorro (Perpetual Help) overlooked the cafe.

“I can’t do this by myself!” she cried to the saint. “I need your help to get this done in time.” And then time stopped. Socorro swore that every time she looked at the clock, the hands had only budged a fraction and indeed, she finished the order and was out the door to deliver on time.

It was time for me to get on the road again. Traveling west, I circled around the great Jemez Mountain range through the towns of Abiquiu, Coyote, Gallina. Looming large on the left horizon was Tsi Ping, or Pedernal as the Spanish called it. Tsi Ping in the Native American Keres language means “flaking stone.” Reportedly there was a large obsidian mine from which tools and implements were traded for hundreds of miles away. The Spanish word means “flint.” Years before, I discovered an amazing summer solstice alignment with Tsi Ping and the setting sun, seen from the Puerto Nambe area in the high country above Santa Fe. That is the subject of another Earth Walks blog entry. For Georgia O’Keefe, the mountain held special significance. She was reported to say that if she painted the mountain enough times (as she did with a mysterious ladder above it in the sky along with a half-moon), she would become one with the mountain and it would be “hers.”

The mountain felt like “mine” on this day as I once again traveled past it. Years before, I climbed the peak, and felt a strong energy that evoked the unseen presence of something I could not quite name at the time. On this day it felt like a directional sign post and good friend waving to me on my journey to Chaco.

I needed a friend because I feel like a refugee, escaping from a troubling work situation with the Santa Fe Public Schools. Close to the canyon the cell phone unexpectedly buzzed with a message from the job. I recoiled and contracted, like a cornered snake that had gone into defensive posture. But then I thought to myself, “Keep your protective spirit shield firmly in place and do not contract in fear of change or new conditions, requirements and adaptations around you. Say ‘yes!’ to all that does not compromise your core values.” And with those words, I arrived in the canyon.

Chaco was still the same bone-dry desert ecology that always seemed so inhospitable to human habitation. It was brutally hot that day, but like every desert, Chaco took getting close to the ground to see the complexity of life that does exist. Ancient cultures utilized beeweed, pinon nuts, rice grass, cactus fruit and other native plants for food, then later cultivated beans, corn and squash. This trio was known in Native America as the “Three Sisters.” When planted together, they worked to help one another thrive and survive, a good metaphor for any community. (See http://www.nativeseeds.org/learn/nss-blog/415-3sisters ) For my food, I foraged through the aisles off my local community natural foods co-op store in Santa Fe which did a good job helping its members thrive and survive.

Later in the day in camp, I sat in the only available mottled shade of nearby low growing cliff bushes and created prayer sticks for friends facing challenges as well offerings to my home. The sticks were decorated with yarn, feathers and other found objects. While they were made, they were imbued with positive thoughts and intentions and then planted in the earth outdoors where winds carried their prayers to all the directions. Kind of like prayer flags in the Buddhist tradition. Creating them in silence was a kind of meditation. I sat, knees bent, “feet standing,” silently winding colored yarn onto the sticks.

I learned how to make the “ofrendas” or offerings from a woman named Maria Elena. She was of Native Mexican Huichol ancestry and had the gift of being a “dream healer,” which meant she could enter into the dream world of a person and offer help and interpretation. As a young child in Los Angeles, where her Mexican parents had immigrated, she occasionally found herself in that dream world, seemingly floating above her bed and having other unusual experiences. Experiences that her parents did not want her to have, as they had immigrated to the U.S. to forge a new and hopefully more prosperous life. So, they put her in parochial school to help her forget the old ways. But Spirit will have its way, no matter where we are.

At school, Maria Elena made friends with a school maintenance man and together they went out to the desert and did prayer and ceremony, helping to further deepen her healing abilities. This secretive time in ceremony and prayer helped her make sense of her natural talents. Maria Elena said that if she had been living in her Huichol community in Mexico, the elders would have recognized her gift and taken her to be trained in the ways of their people. Fortunately for me and many others, she did not lose that gift and indeed was willing to share her healing ways.

I thought of her now at Chaco and acknowledged the gift of her teaching. As I sat in calm, silent gratitude a two-foot snake unexpectedly and quietly sl

id her way under my legs. It was a total surprise, yet in another way it wasn’t, since I’ve had so many encounters like this in nature. I stopped working on the prayer stick as the snake stopped among the colored balls of yarn and feathers. She looked up at me and blinked. I winked back, neither of us expressing any trepidation. Chaco had always shared its mysteries and magic with me, and this was another one of those moments.

For some indigenous cultures, the snake is the most sacred of animals as she travels with her heartbeat so close to that of Mother Earth. In the system of Medicine Wheel earth astrology by Sun Bear and Wabun, my totem animal is the snake. https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Medicine-Wheel/Sun-Bear/9780671764203 Unlike many European concepts of the snake, in Native America this creature is revered for its power of transformation. The shedding of skin is a powerful metaphor for our ability to transform our innermost being, bringing the lessons we learn in life into harmony. And the snake has something else special to teach–it is the only creature that travels through life with its heart in close contact with the earth.

I reflected on all of this as I bumped along the washboard dirt road from Chaco, thinking about the snake’s advice to experience the world willingly and without resistance. Sun Bear and Wabun wrote, ” (the shedding of Snake’s skin)…is the knowledge that all things are equal in creation and that those things which might be experienced as poison can be eaten, ingested, integrated and transmuted if one has the proper state of mind…which can bring about a balance of passion, vitality, dreams, leadership, wisdom and resolution.” That certainly would help in my job challenges, so I resolved to be more like the snake and stay close to the ground, listening to the messages of my heart and that of mother earth.

Walk in Beauty: Canyon de Chelly, Arizona

It was late September 2016 and the planet was in its eternal autumnal dance of change. Eleven people including my nephew Greg and I were on an Earth Walks journey from Santa Fe westward to the 1,000-foot red sandstone canyons called De Chelly by the Anglo world and Tseyi by the Dinè (Navajo) people. Our path took us around the Jemez Mountains west of Santa Fe where only a million years ago its massive volcanic explosion sent chunks hurtling as far away as Nebraska.

Onward we went through high desert rolling hills, tall pine forests and open plains, home to herds of elk. We passed the turn to Chaco Canyon, where amazing structures constructed with precise astronomical alignment are found along with hundreds of underground ceremonial kivas, all which represent an advanced complex social and spiritual organization. https://www.nps.gov/articles/chaco.htm

Once we escaped the clutter of billboards, oil rigs, auto salvage yards and cookie cutter fast food eateries in the Farmington-Bloomfield area, we saw a huge looming, almost otherworldly land form in the hazy western horizon. Its silhouette was dark, starkly solitary, and almost brooding.

It is known as Shiprock and indeed looked like a gigantic ship, impossibly frozen in a sea of desert. ( Photo by focalworld.com ) One story I heard was that to the Dinè, it is the legendary great bird that brought them from the north to their present lands. We traveled on, the land rising to forested mountains, dropping again to bare sandstone cliffs of the Lukachukai Mountains. We were nearing our destination when suddenly without warning, the canyon opened visibly before us.

On our first full day, we were immersed in the canyon on a journey with Beauty Way Jeep Tours https://beautywayjeeptours.com/ when my watch stopped. Me, who was leader of the pack and so focused on dates, itinerary, agenda, checklists and movement of participants at specific intervals of time. But we were in some ways in “time without time” and a wristwatch actually seemed like a superfluous anachronism. I wasn’t prepared for the spirit of the land next taking away my prescription glasses, but I didn’t even miss them until hours later.

The following day we were back in the canyon gathered around Kathryn Pemala who knelt before the web of her hand crafted loom, weaving threads of wool from her sheep into a multi-colored tapestry of wind, sunlight, stars and ancient stories of hope, tragedy, sadness and laughter. Kathryn lived on this family farm all her life, raised sheep and goats, grew fruit trees, corn and a family as had generations before.

“I hear the songs and stories. That’s why I weave,” Kathryn told us. “Plus it’s good physical work.” We came to hear her story, but also to help on the farm, so we got busy with physical work.  Dust flew, people sneezed, goats greedily munched the weeds we chopped and everyone chatted and chuckled. It was time to go all too soon, but we crammed into crowded jeeps amidst smiles, appreciation and promises to return next year.

Dust flew, people sneezed, goats greedily munched the weeds we chopped and everyone chatted and chuckled. It was time to go all too soon, but we crammed into crowded jeeps amidst smiles, appreciation and promises to return next year.

One can feel an eternal return in the canyon, however—a coming and going and coming again of countless seasons that have shaped both the land and the people who live within her protective embrace. It was hard not to feel a part of this immensity, to shed our limited physical skins and become a part of the place—to Walk in Beauty, as the Dinè say. It was especially so on our last night as we overlooked the great spire of Spider Rock, full moon rising on the eastern horizon.

Oh, and that watch of mine that stopped? I took it to the jeweler who checked the battery and found nothing wrong and returned it to me ticking right along. And the glasses? On the second day, our group kindly stopped in the side canyon where I thought I might have dropped them, and we fanned out in a search party. Suddenly overhead, a red tailed hawk circled and sent out its screeching call, resonating against the canyon walls.

Soon after, the glasses were found where they had spent a night under the nearly full moon. “New vision,” someone said.

The Welcome Fire

“Once you’ve walked and left footprints in the canyon a part of you will always be here,” Daniel said. What he didn’t say was that Canyon de Chelly, Arizona will call you back. And so, it has for over 30 years.Every return has been different yet somehow always the same. On one occasion I was joined by 13 others. Some had been to the Canyon before, some never. But all had heard the call. It was October, 6 a.m. and dark in Santa Fe when we started the journey, none of us including me sure of what lay ahead but truly ready to go on the adventure.

First, we offered cornmeal to feed the directions, the morning, our journey, the vehicles and each other and all others. It was an Indigenous tradition from the Southwest I had been shown to do, and almost every early dawn whether it was downtown Washington, D.C., Kolkata, India or my own backyard in Santa Fe, I had done so. Dinè (Navajo) elder Annie Kahn, in the spirit world as of this writing, once led me in dawn prayer, when the stars were shining and a thin line of light threaded its way across the eastern horizon. She said it was a special time of “Hòzòn” (beauty in the Dinè language) when prayers could be sent and heard most clearly. Annie was and is still a light in the dark for me and many others.

Offerings made, we traveled on past pine clad mountains, the looming flat-topped volcanic Tsi Ping (Pedernal) peak made famous by artist Georgia O’Keeffe, through red sandstone cliffs of Gallina, the rolling plains near Regina, past billboards, gas stations and fast food eateries of Bloomfield and Farmington.

Offerings made, we traveled on past pine clad mountains, the looming flat-topped volcanic Tsi Ping (Pedernal) peak made famous by artist Georgia O’Keeffe, through red sandstone cliffs of Gallina, the rolling plains near Regina, past billboards, gas stations and fast food eateries of Bloomfield and Farmington.

We stopped as if compelled by some invisible force near the visually stunning and dramatic immensity of a sharply jagged dark peak commonly known as Shiprock. No ships around here, though. It was a misnomer. The Dinè named the peak Tse Bit’a’i, “rock with wings” which refers to the legend of a great bird that brought the Dinè from the north to their present lands. Other traditional stories surround this mountain which thrusts starkly upwards into the cobalt blue sky with its “wings” of volcanic rock radiating north and south from the central formation.

Traveling westward we snaked our way over the Lukachukai Mountains, with stunning views towards Tse Bit’ a’ i’ in the east, then dropped down through massive red sandstone cliffs to the west, eventually reaching the mouth of Canyon de Chelly and the Dinè family who would be our guides for four days.

From the Earth Walks I remember: