|

|

|

|

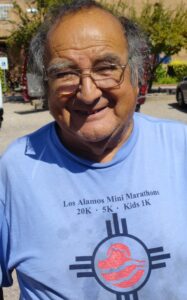

I got to know Tio Manzanares Tio’s Biography of the Abiquiu area one winter when I was instructor at Ghost Ranch Conference Center for the “Earth Walks” the Spirit of Place” college Jan Term course in 2002. He impressed me as a sincere, humble and jolly person with many magical stories to tell. To this day I don’t know which story was “true” or not, but  what story that anyone tells is actually “true,” including mine? For me, what was true were the genuine smiles he engendered, the noble yet powerfully simple wisdom he imparted and the history of this part of northern New Mexico that he experienced and shared. As a younger man, Tio had worked for artist Georgia O’Keeffe, so he had many recollections of this somewhat enigmatic icon to share. “True” or not, they were fascinating, amusing and one person’s insight into O’Keefe’s world.

what story that anyone tells is actually “true,” including mine? For me, what was true were the genuine smiles he engendered, the noble yet powerfully simple wisdom he imparted and the history of this part of northern New Mexico that he experienced and shared. As a younger man, Tio had worked for artist Georgia O’Keeffe, so he had many recollections of this somewhat enigmatic icon to share. “True” or not, they were fascinating, amusing and one person’s insight into O’Keefe’s world.

Tio accompanied a number of our Earth Walks and on one he shared that during his days as a stone mason, he would watch and listen carefully and select only those rocks and stones “that wanted to go with me.” That seemed like such good advice for us all, not in just selecting stones for a garden wall but in making daily decisions in our lives.I wrote the following for an edition of the Northern New Mexico Community College literary magazine “Trickster,” before Tio’s passing in 2018:

Honest to Goodness or “With Good Attitude Comes Good Weather” —Tio Manzanares

I would have never thought ghosts, spaceships and Georgia O’Keefe had anything in common until I met Tio Manzanares, stone mason, musician songwriter and story teller from Abiquiu, New Mexico. Are the stories Tio tells true? That’s for you to decide. Reality is completely overrated, honest to goodness.

I was teaching at Ghost Ranch conference center near Abiquiu when someone said, “There’s a local storyteller today and everyone’s invited.” My course was on the cultural and spiritual traditions of northern New Mexico so you can bet I went to hear him at his Elder Hostel presentation. But turns out it wasn’t just hearing him—it was seeing him. Something about his eyes. A twinkle, yes, but more like a silent chuckle just before his whole face ignited into laughter and a smile, his eyes disappearing into tiny slits. My curiosity was ignited as well. Anyone who’s got a smile that big has something they’re not telling—or something they should be telling. In Tio’s case it was the latter, and I had to meet him.

At dinner time I headed for the dining hall to find Tio. Just outside the hall are huge elm trees where years later I would find myself on a late summer afternoon playing my Native American flute and standing with Santa Clara Pueblo elder Rina Swentzell, a respected scholar, architect, author and friend. As I was playing, the twittering of a little bird hopping from branch to branch caught my attention. I finished playing and without thinking about it, turned to Rina and said, “Happy birthday!” She looked astonished and asked how I knew that this day was indeed her birthday. My answer? “Honestly, I didn’t know. But a little bird told me.”

As I entered the dining hall, there was a loud cacophony of noise from people busily engaged in conversations from their classes, speculations on the weather and a thousand other things. The hall was a large open space with a somewhat aging collection of tables, chairs and food serving stations all looking out through framed picture windows across open fields to the southern expanse of the Chama River Valley. Ranch hands with dusty jeans and weathered boots munched hamburgers next to carefully coiffed Texas gals adorned with the appropriate amount of turquoise jewelry who sat next to college kids with tattoos and swatches of rainbow streaked hair. Some people sat silently by themselves. All were welcome at the table.

I had two things in mind: supper and Tio. I found both, one that satisfied the body and the other that left my curiosity happily hungry for more. I spotted Tio, who to me looked like a magical duende, a Santa Claus off duty: hair tousled from the winds, well-worn jeans, shirt not totally tucked in with an occasional spot of chile. New Mexico chile, of course. I made my way over to his table, introduced myself and asked if I could sit and visit. “Of course!” he said, smiling as he waved me to the open seat next to him. I sat down, but I soon learn I wouldn’t be sitting much longer. I’d be dancing.

A few days later my Ghost Ranch class and I were at the cafe called Socorro’s in Hernandez, an area not far from the ranch and Abiquiu. Plates of food came steaming hot from the kitchen–enchiladas smothered with the flavor of New Mexico—red and green chile, onion, cheese, frijoles. Posole, the puffed corn stew that takes over where hominy leaves off, shoulders up to spicy rice and the whole combination ended up dancing off the plate and into my mouth. Our group was dancing too—or trying–to the songs of Tio and his longtime friend Socorro who ran the restaurant.. Her husband and son were belting out a lively instrumental backup on guitar and trumpet and in the tiny cafe the sound was deafening. I and the class didn’t have a clue how to dance to this music, but were are dancing anyway, happily providing entertainment for locals in the cafe. Smiles abounded amidst the pounding beat, spicy chile sauce and Spanish canciones.

I was told that Socorro was a major mariachi diva back in the day and I believed it. Her voice boomed out louder than the instruments as she smiled widely while waving her hands rhythmically in the air. She’s had on her kitchen work clothes and apron but in my eyes she was spotlighted on stage, glittering with silver braid around a black gabardine jacket and skirt, complete with a white cotton blouse and big bright red bow tie.

Mariachi music is often called la musica de la gente (music of the people), evoking stories of triumph and sorrow, betrayal and heroism, life and death. It’s the strand that weaves together baptisms, graduations, weddings, reunions and festivals of all kinds, the gorilla glue that’s been keeping generations of many northern New Mexicans together. And it’s the music Tio said he’d been making since he was two years old. For good description of mariachis see: https://www.newmexico.org/nmmagazine/articles/post/mariachi-79132/

“The older generation was very musically inclined.” Tio said. “It was a way to relax. There were lots of dances where local bands played.” At some point he began to record music of his own on 45 rpm records but ironically had no player on which to listen to them until some unknown person gifted him with one on his doorstep. Gifts from unknown and unseen angels—it’s a theme that runs through Tio’s life. But he had to deal with some not so better angels when it came to getting his music in the public ear.

“I had bad experiences with the Spanish language stations,” Tio shared. “They had an unwritten rule: you pay to play. The FCC said you should support the community but they weren’t playing local music. I’m embarrassed to say it was the ‘gringo’ stations that agreed to air my music every now and then.”

Back in Tio’s early years a traveling troupe of entertainers wound its way up from Albuquerque and into the isolated villages of northern New Mexico, bringing music, cuentos y dichos—modes of storytelling that kept the culture vibrant. Imagine the 1957 hit Broadway show Music Man with a local version of Robert Preston rolling into town—maybe not with 76 trombones, but still with lots of fanfare and great anticipation. Tio joined the troupe dressed as a clown and acting every bit the part. He must have been in his perfect element among the puppets and ventriloquists, musicians and assorted members of the traveling troupe. Tio’s grandfather was also a clown in the shows. They say humor is the best medicine and so it must have been for him.“He never smiled except when he was a clown with the Maromero,” Tio recalled, “and then only once in a while.”

As he got older, Tio stepped outside his familiar world, venturing into the Los Angeles music scene a bit. During high school he worked for a Spanish language radio station and traveled around the Southwest as a news reporter. He even tried out Catholic seminary for a few years. “But honest to goodness with the temper I have, I would tell the priest off.”

For most of his life, though, Tio kept close to the land near the village of Abiquiu, where he was born in 1948. A starkly beautiful area, the valley is sheltered by shoulders of tall red, ocher and gold mesas. From some places you can see the flat-topped volcanic butte known as Pedernal to the Spanish, and Tsi Ping to the original Pueblo Keres people. The Chama River originating in Colorado snakes its way through the valley amidst a tangle of cottonwood trees, salt cedars, willows and high desert cactus and plants that have adapted to the sometimes-punishing winds and extreme temperatures. Occasional rain storms can be fierce, flooding everything in their path.

The now famous artist Georgia O’Keeffe made her way to this harsh and beautiful desert environment seeking quiet and inspiration for her work in 1929. She first landed in Taos, then Ghost Ranch and finally settled in Abiquiu. Tio worked for her part time from 1959 to 1971, helping her around the house and garden.

Tony Vaccaro, Georgia O’Keefe with “Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow” and the desert, 1960. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Courtesy of Tony Vaccaro studio.

“Miss O’Keeffe loved nature. She had me come to work early in the day so we could watch the sunrise. She really taught me to love nature,” he said. “When I drove her out somewhere to paint, she wouldn’t just sketch anything, only do a real painting. And she said she ‘just made the mountains.” One time when he drove her out to paint the landscape, she told him she would paint the Pedernal (original name by Keres First Nation Pueblo of Cochiti is Tsi Ping) enough times that it would become “hers.” In a way her determined goal came true: after her death in 1986, her ashes were spread atop the iconic volcanic feature. But instead of the mountain becoming hers, it was more like she became part of the mountain.

Tio remembered that Miss O’Keeffe would repeatedly urge him to be independent, go to school, and to have the discipline to do whatever he wanted in life. He took her advice and put that discipline to work. For over 20 years (1972-98) he was a stone mason, hauling 8,900 loads of rock and going through 42 trucks. He was given the secret of how to do the work by another stone mason. It was hard labor for sure, but if he’d only known what he knows now it would have been easier, he says.

“An Indian friend once told me to listen to what the rocks were saying. I thought that was silly. A rock doesn’t have any understanding. But it was actually me who didn’t have the understanding! Once I caught on and figured it out, the rocks were gentler to me. I stopped smashing my fingers and could move them more easily. I was told by the rocks not to clear all of them out of one area. Cooperate with nature and leave some for the next generation.

“Everything in nature has a way of working in harmony with humans. But people have to do the right things so nature will do its part. With good attitude comes good weather. Not just one person should do this but thousands.” Then added some more sage advice: “Just try listening to a 500-year-old cottonwood tree. You have to listen a long time and be at ease and serene in your life. Listen with a good heart and put away negativity. A tree is a very sensitive thing; but it and anything in nature will respond. If we pay attention to certain signs, we can tell when things are going to happen.”

But Tio wasn’t always paying attention. “Sometimes I was sure my truck had broken down because some of the stones I had were not intended to move from their spot.” One cold winter late afternoon his truck became disabled in a remote and isolated location. Tio was worried, unsure of what to do. There was no one in sight and the darkness was quickly clamping down around him. Suddenly in the distance he saw headlights of a vehicle, coming closer to his location. Then he could hear tires slowly crunching on the frozen dirt road. The car arrived and out stepped a total stranger.

Inquiring as to who he was, the stranger cryptically replied, “I’m just helping out people who get stranded.” And where are you from, Tio asked. The reply, just as inscrutable: “Oh, a place you wouldn’t even know about.” The stranger walked back to his car and returned quickly with the exact tools and part needed to get Tio’s truck up and going. Then he departed into the dark. Quickly Tio climbed the hill to watch where the stranger’s car headed but there were no lights and no sound of a vehicle in any direction.

Tio’s life was filled with the kind of inscrutable that some would call angels or visitations of divine apparitions. Towards the end of his stonemason career, he smashed his hand severely, crying out to the patron Saint Jude of Desperate and Lost Causes, “If you think you can change my life, do it!” In a week he had a different job and ever after he kept a candle lit at the foot of a statue to the Catholic saint. “Maybe he’s the one that helped me out on that cold winter afternoon when my truck broke down,” Tio mused.One time he was watering plants outside his house and heard someone call his name. No one was around, but then he saw a “very pretty young lady floating in the air above the trees.” He felt fearful at first, but then she spoke in very gentle soothing tones. “She talked about a lot of things that would happen in the future and showed me a large animal chewing on the world,” he said. “Then she told me I was going to be very sick but that she would take care of me and I’d live past 95 years old.”

Not all his close encounters were with the metaphysical, but they were definitely tinged with the mystical as well as the amusing. Like his encounter with what he called the “bus queen.” Tio once owned a school bus which he was tinkering with to turn into a traveling van or even a place to live. But he gave it up to a homeless man who was living in a car and struggling with dialysis. He was on a search for another school bus when he met a woman from Colorado who said she had over 100 buses and would give him one. Twenty-two years later the Colorado woman called and told him, “I might take a long time but I don’t forget.” Soon after he got his new bus.

Then there was the Halloween night when neighbor boys pulled a trick and partly painted his truck black and white, “like a Holstein cow or the Gateway computer logo.” The truck had been repeatedly revived with 10 motors and had “a million plus 32,000 miles on it.” The only original things on it were the cab and doors. Tio’s response to the prank? He went directly to the boys’ house (correctly surmising who the culprits were), sternly confronted them in front of their parents and then gave them a Halloween trick or treat of his own.“You did a good job,” he said with I imagine a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. “But it wasn’t good enough. I want you to finish painting the truck.” They did. The story got around the Abiquiu valley and traveled with Tio wherever he drove the Gateway Holstein cow truck.

There were also aliens from other worlds. Tio said he had encounters himself, but an uncle who was a sheepherder near Roswell had one to be remembered for sure. As Tio told it: “My uncle was out with the sheep one day when he saw a big flash of light and heard a crashing sound on the land. He went over to see about the commotion and found a strange looking vehicle on the ground and odd little men in brown skirts running around like they were in shock.” Tio said almost immediately his uncle was visited by government agents in large black cars who told him to leave the area and that they would take over from there. This was in 1947, the date most ascribed to the Roswell Incident, which the U.S. Military claims was a nuclear test surveillance balloon. Fact or fiction? Military operation or extraterrestrial visit?

In recent years, Tio stepped a bit more out of the radar to live on a patch of high desert land near Abiquiu. He was harder to find, out of cell phone range. No land line, but on the land for sure. He mailed me directions to his place, and one day I and some visiting friends decided to find him. It felt like a treasure hunt with cryptic clues: turn past the second fence post after the third dirt road; don’t take the left fork, it will get you lost; look for the large juniper tree on your right….and so on. I think we did take the wrong fork, had to backtrack, and had to be careful not to get the tires stuck in an arroyo with deep sand. Climbing up a hill on the rutted road, we found the remote valley where his summer home—a converted school bus—and his winter home—a metal shed—were situated. As we drove up, Tio emerged from the bus, his always smiling self, to greet us. On a tour of the place, he shared that friends had paid to install a small propane heater in the shed and one day a set of brand new mattresses mysteriously showed up at the doorstep. Another of those inscrutable gifts from the mysterious unknown that have visited Tio throughout his life.

As remote as it seemed, I knew that if I could fly like a raven I could take a short direct path and flap over the McMansions bulldozed into the hills and former farm fields of the Abiquiu Valley. It got me thinking. A lot lies beneath the surface of the iconic red chiles hanging at the front door, like at my own house. Generations of colonialism and traumatic cultural conflict continue to the present day and show up in many sad and distressing ways here. Economic hardship in New Mexico is pervasive, so much that people sometimes say when the nation’s economy goes for a deep dive, it isn’t noticeable here. I suppose I’m an unwitting part of the gentrification and social displacement, a product of privilege in my own way. As I said, it got me thinking.

Some people might see Tio’s life as one of poverty, wonder how he could live like that and then they might pass on by to find photo opts of the intensely blue skies or Georgia O’Keeffe’s house in the village or attend seminars at Ghost Ranch like the ones I taught. I was reminded of British author Rodger Housden’s experience writing Sacred America: the Emerging Stories of the People. Traveling across the country he stopped in Santa Fe and for some inexplicable reason he was interviewing me for the book and had joined one of our Earth Walks events. He shared this insight: “I was in Moab Utah trying to find a woman who local people told me I should meet due to her profound insights. Eventually I made my way to her tiny trailer in the desert. There wasn’t even room for me to sit down, but I felt like I was in the grandest palace in the world. I’ve been in those palaces, too,” he added, “and have felt literally claustrophobic by the smallness of spirit.”

As our visit continued, Tio lamented, “So many places have been taken over by newcomers. There is more dishonesty, deceit. They try to regulate the old timers with laws and restrictions. They make honest to goodness people smaller, calling them old fashioned because they are kind. They are doing things that aren’t environmentally sound, like using dangerous pesticides for farming rather than the old natural methods.”He was quick to add, though, that “there are a lot of good newcomers.”

Tio didn’t invent a cure for some disease, travel around the world in record-breaking speed or land on the moon. He did, however, help keep traditions of New Mexico alive. Like many native New Mexicans he was anciently rooted in the spirit of place and the power of kindness, seasoned with fierce confidence, a good dash of humor and belief in miracles.“A stone mason got me started with doing that kind of work early on,” Tio said. “It’s like putting a puzzle together, finding the pieces that fit. It’s helped me deal with my problems of life. The rocks have to fit in a special way, just as things had to fit together in a certain way in my life so I could do what I wanted to do.”

Honest to goodness, indeed.