(This is next in a series of highlights from my Earth Walks experiences over the years.)

Coyote and the Pyramids of Mexico

I traveled to the Great Sand Dunes National Monument in southern Colorado for first time in July 1990. The tallest dune is 750 high, which is over seven stories.  At the visitors’ center I learned about the fate of a coyote who died in a well of the dunes. He had ventured into one, perhaps chasing a bird or rodent, but could not get out. Although coyotes are sly and cunning and quite bright creatures, this one did not realize that if he had used the principle of sacred geometry and walked in a spiral direction up the sides of the dunes, he most likely would have escaped. (Watch birds circling upward through wind currents you can see this principle in action.) Climbing in a straight, linear direction was of no help–obviously. Maybe in his next life Mr. Coyote would know that traveling in a straight path is not always the quickest way to your goal. It’s something I keep relearning in this life myself.

At the visitors’ center I learned about the fate of a coyote who died in a well of the dunes. He had ventured into one, perhaps chasing a bird or rodent, but could not get out. Although coyotes are sly and cunning and quite bright creatures, this one did not realize that if he had used the principle of sacred geometry and walked in a spiral direction up the sides of the dunes, he most likely would have escaped. (Watch birds circling upward through wind currents you can see this principle in action.) Climbing in a straight, linear direction was of no help–obviously. Maybe in his next life Mr. Coyote would know that traveling in a straight path is not always the quickest way to your goal. It’s something I keep relearning in this life myself.

His story reminded me of my own years before at Chichen Itza in the Yucatan of Mexico when I had scrambled laboriously up the side to the top of the Mayan Kulkulcan (El Castillo) pyramid. While I ate my sack lunch, I devoured the words of a Mexican anthropologist whose book I bought at the visitors’ center told of the ancient priests ascending the pyramids in a zig-zag fashion, conducting ceremony on top, then ascending the opposite side in an opposing zig-zag. Putting the two paths together formed a diamond pattern, which was also found on the back of the rattlesnake. The serpent was a central cosmological icon for the Mayas. In fact, at summer solstice the noon day sun casts shadows down the steps of the pyramid creating the effect of these diamond shapes, ending in the huge stone head of the serpent at the bottom.

I wrote the following about that experience:

The asteroid slams into the ocean creating an immense cataclysmic tsunami. The event profoundly shapes the course of global history over millions of years and forms the Yucatan peninsula of México, a flat, almost featureless massive limestone shelf carpeted with densely grown selva. For reasons not completely known, huge pyramids begin rising above the jungle forest, fashioned from the limestone floor. They are a marvel of architecture, mathematics, astronomy and human endeavor.

I sit high atop one of these, Kulkulcan, at Chichen Itza, watching tourists claw like insects up the 95-foot structure. They clutch the safety chain on their route, unaware of a mysterious giant serpent just beneath their feet. Their focus is on cameras, picture taking and conversation. Mine is on lunch and a little pamphlet that will create a tsunami in my own consciousness. Sandwich in one hand, pamphlet in the other, I read that the classic Mayan culture spanned 2,000 years (1000 BCE-CE 1542). The Mayans devised a calendar system more accurate than the Gregorian calendar of 1582 and their writing skills surpassed all others in the New World. Somehow, they developed the concept of zero. It was an amazing period of art, scholarship, political and religious fervor.

The pamphlet I read purports that Mayan priests ascended the pyramids with a predetermined zig zag pattern, conducted ceremony, and then descended the opposite side in another diagonal. The two diagonals juxtaposed formed the diamond design on the rattlesnake, the Kulkulcan deity. Each of the four stairways on this pyramid has 91 steps, adding up to 364, with the upper platform equaling 365 for the number of days in the year. Guarding the bottom level is a huge stone serpent head. During the spring and autumn equinoxes, the sun casts a series of triangular shadows against the northwest balustrade, creating the image of a feathered serpent.

I finish my sandwich and finish the pamphlet. Wanting to do the ancient diagonal walk, I find myself oddly hesitant. After a deep breath, I step off into the unknown. First thing noticeable: My feet perfectly fit the rough, narrow limestone steps as I walk diagonally in the zig-zag pattern. No safety chain needed. Then, halfway down, an unexpected encounter: a man dressed in black, carrying a falcon on his arm, ascending the pyramid, also diagonally. Time seems to stop in the silence. Our eyes meet in mysterious recognition. Time begins again and we continue on. For some reason, I don’t look back to see if the man and falcon are “really there.” Somehow it doesn’t seem to matter. Later I learn that our encounter was at the level of the pyramid where a jade jaguar statue, symbol of strength and power, had been discovered.

I reach the last step and pause for reflection at the stone carving of Kulkulcan. Standing next to the statue is a visiting tourist who indifferently crushes out her lit cigarette on the serpent head. One kind of light goes out, but another has ignited within me to help illuminate the unexpected zig-zag mysteries of life ahead.

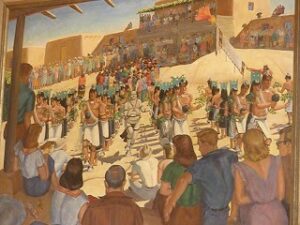

(Years later, I dreamed of being a priest on top of the Kulkulcan pyramid at Chichen Itza in Mexico. In it, I was inspired to bring the other priests off the top of the pyramid with me to the people assembled below to do ceremony and prayer with them. I am most certain that I was assassinated for this violation against the hierarchical power structure. Was it a dream, or was it perhaps a past life?)

(Years later, I dreamed of being a priest on top of the Kulkulcan pyramid at Chichen Itza in Mexico. In it, I was inspired to bring the other priests off the top of the pyramid with me to the people assembled below to do ceremony and prayer with them. I am most certain that I was assassinated for this violation against the hierarchical power structure. Was it a dream, or was it perhaps a past life?)

On my way back home to Santa Fe, NM, I stopped for a visit in Mexico City. The city’s metro rail system was a marvel of efficiency, cleanliness as well as an educational experience. In one passageway a magical holographic exhibit with black lights illuminated a journey through the stars. After emerging into the sunlight above ground, I made my way towards a looming conical shape in the distance, the ultra-contemporary Basilica of Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, built adjacent to original historic church.

On my way back home to Santa Fe, NM, I stopped for a visit in Mexico City. The city’s metro rail system was a marvel of efficiency, cleanliness as well as an educational experience. In one passageway a magical holographic exhibit with black lights illuminated a journey through the stars. After emerging into the sunlight above ground, I made my way towards a looming conical shape in the distance, the ultra-contemporary Basilica of Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, built adjacent to original historic church.

The popular story is that the Virgin Mary appeared to a Nahua man named Juan Diego in December 1531 on Tepeyac Hill, north of Mexico City, where there was a shrine dedicated to the female Aztec earth deity Tonantzin. To this day, in Nahuatl-speaking communities (in other communities as well), the Virgin Mary continues to be called “Tonantzin” and her appearance is commemorated on December 12 each year.

The figurine pictured above from the Mexico City National Museum of Anthropology is believed to be of Tonantzin, which reportedly means “Our Sacred Mother” in the Nahuatl language. Tonantzin continues to be connected symbolically to fertility and the earth. There are many myths surrounding the Virgin of Guadalupe but she has been recognized by the Catholic church as a manifestation of the Virgin Mary. The Virgin of Guadalupe has become a national symbol of the Mexican nation and she is viewed by many to be a special protector of Native American people.

The Virgin eventually replaced the Aztec Earth Mother goddess Tonantzin in shrines throughout the countryside. Her image is found throughout the world, especially in the Southwest and New Mexico in many shapes and forms, from tattoos on the back of bikers to pillows and banners. To me, however, she represents the divine feminine, great mother of the universe.

The original as well as the new church sit in sharp contrast to the shocking poverty of the people who beg for a few centavos at its doorstep. Would La Senora really have wanted all this opulent fuss? What would Christ have said?

The original as well as the new church sit in sharp contrast to the shocking poverty of the people who beg for a few centavos at its doorstep. Would La Senora really have wanted all this opulent fuss? What would Christ have said?

Like other visitors, though, I got on the constantly moving conveyor belt to get a glimpse of the cloth with Mary’s image. I entered the Basilica as a haunting cancion and the mass began and I was on a mission: to light the candle in my hand at the main altar. With the kind help of a local woman and nun, I received permission from one of the male priests officiating at the altar (of course, no women on the altar, even though this was a temple to honor a woman) to light the candle. “Not normal,” the priest said in a friendly way, but he did indeed light it from one of the altar candles. (I love breaking taboos!) Shielding it carefully from the breeze, I retraced my steps around the enormous hall, exited “stage left” and placed my candle at a tiny humble shrine outside that was embedded in the hill.

From the oppressive glitter of the Basilica, I trod zig-zag (like the ancient priests did at the pyramid of Kulkulcan at Chichen Itza off the hill to make a private offering to Tonantzin with cornmeal. As the atole rose to each direction in the gentle breeze I felt a mixture of joy, sadness and thanksgiving.

Back in the Metro, I encountered an amazing photographic display that started with an image of human skin, then delved deeper into the microcosmic details to the very quasars and atomic structures as we understand it now. At one point the skin looked like great canyons and valleys like those of distant planets or the Southwest of the United States. I was tired from traveling and got disoriented, but a kind Mexican man helped me back in the right direction. Running late, I arrived at the airport, checked in and walked to the gate precisely as they began to board….I was on my way home.

I was on a solo journey to Chaco Canyon August 11, 2012, taking a favorite walk from the Great Kiva Rinconada to the mesa above the kiva and the ancient site of Tsin Kletzin. The subterranean Great Kiva was once utilized for religious activities and ceremonies. It had 39-foot passageways from the underground structure to above ground levels. Casa Rinconada is one of the many buildings in the Chaco area that have documented astronomical alignments. Many know the Great Kiva for the archeoastronomy event that occurs on summer solstice. PBS video

I was on a solo journey to Chaco Canyon August 11, 2012, taking a favorite walk from the Great Kiva Rinconada to the mesa above the kiva and the ancient site of Tsin Kletzin. The subterranean Great Kiva was once utilized for religious activities and ceremonies. It had 39-foot passageways from the underground structure to above ground levels. Casa Rinconada is one of the many buildings in the Chaco area that have documented astronomical alignments. Many know the Great Kiva for the archeoastronomy event that occurs on summer solstice. PBS video